Extreme Climate Survey

Scientific news is collecting readers’ questions about how to navigate our planet’s changing climate.

What do you want to know about extreme heat and how it can lead to extreme weather events?

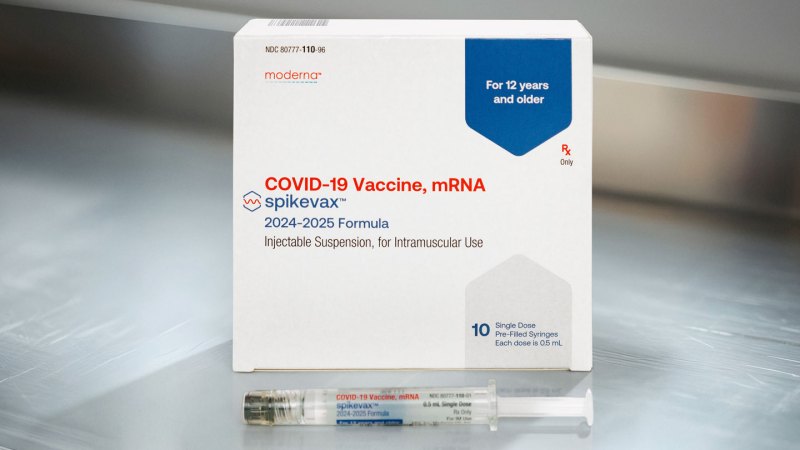

The distribution of the new vaccines comes just before a program that temporarily pays for vaccines for the uninsured expires at the end of August. That leaves about a week for people without insurance to decide whether to get a shot now at no cost.

“If this is your chance to get the vaccine, and after that, you’re not sure if you’re going to be able to pay for it, I would absolutely get the vaccine now,” says Kawsar Talaat, an infectious disease doctor. at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health.

Here’s what else you need to know about the new photos.

How do the updated vaccines differ from last year’s version?

They’re exactly the same vaccine, except for one difference, Talaat says — the type of virus that’s targeted. Last year’s releases were aimed at the omicron XBB.1.5 variant that caused most cases in late winter 2022 and spring 2023.

The new mRNA enhancers target the KP.2 microarray variant (also called JN.1.11.1.2), which accounted for about 3.2 percent of cases in the United States from August 4 to 17. Two other omicron variants, KP.3 and KP3 .1.1, together account for nearly 54 percent of cases during the same period. Another variant known as LB.1 caused 14 percent of cases. And an alphabet soup of other variants circulates.

Novavax’s updated vaccine targets the JN.1 variant. This is the parent variant of KP.2, KP.3 and LB.1. The variants differ by just a few points in their spike proteins, the knob proteins that the coronavirus uses to attach to and enter cells. But the descendants of KP and LB.1 may be slightly more transmissible because these changes help the newer variants avoid immunity from older versions of the vaccine and from infection with earlier variants of the coronavirus. It takes longer to reconfigure protein vaccines than mRNA vaccines, so Novavax had to go with the older version of the virus. Elsewhere, Moderna is making a JN.1 version of the vaccine, the company said in a statement.

This is the third time the vaccines have received updates to more closely match the circulating versions of the virus. Each time the virus has been a few steps ahead, but the shots have provided protection against serious disease, especially for the elderly and people with health conditions that put them at increased risk.

Infectious disease doctor Carlos del Rio says he would like to see high vaccination rates for everyone over 65 because those people are at higher risk for hospitalization and serious illness. “Vaccination continues to be one of our main strategies in [managing] COVID,” says del Rio, of Emory University School of Medicine in Atlanta. “And maintaining immunity is important.”

When should I get the new COVID-19 booster?

Maximum protection against the virus lasts several months after fortification, says Talaat. So “even if you get the vaccine now, you’ll likely have protection by Thanksgiving and Christmas.”

The US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommends getting the vaccine sometime in September or October, depending on what works best for people, agency director Mandy Cohen said in an Aug. 23 call with reporters. “The important part is making it happen.”

People who were infected in this summer’s wave are probably still protected from repeated infections, Talaat says, and can wait until the fall to get their updated vaccine. While it is difficult to predict exactly how long the current surge will last, test positivity rates and viral shedding levels are still rising (SN: 20/9/23). “Covid is still killing a lot of people,” she says. “We may not hear of it again, but it is not gone.”

Children returning to school can lead to a new round of infections. Only 14 percent of children ages 6 months to 17 years are up to date with the 2023–2024 COVID-19 booster, according to the CDC. And although more than 80 percent of adults 18 and older have received at least one shot, the number of people who continue to take boosters has dropped significantly. Only 22 percent of people in this age group received a dose of the 2023–2024 COVID-19 vaccine, the CDC reported in its most recently updated data in May.

How long does the shock protection last?

Many scientists have investigated this question. A large study looking at evidence of antibodies against the coronavirus found that by the fall of 2022, more than 96 percent of people in the United States had immunity from vaccination, previous infection, or both.

But immunity can decrease. For example, last year, people who received the XBB.1.5 vaccine in Europe had fairly good protection against hospitalization from COVID-19 in the first month or so after vaccination. The vaccines were about 69 percent effective 14 to 29 days after inoculation, researchers reported Aug. 15 in Influenza and other respiratory viruses. Effectiveness dropped to 40 percent 60 to 105 days after vaccination. Part of the decline in effectiveness was due to the rise of new JN.1 variants.

But protection doesn’t just fall off a cliff. The new work provides evidence that shots actually provide long-term benefits. The scientists conducted an in-depth analysis of the immune responses of about 500 people over three years. Their results suggest that while the vaccine induces an initial boost of antibodies that tends to fade rapidly after a few months, antibody levels then stabilize, the researchers reported in Immunity in March.

Updated versions of vaccines can further increase that protection. Pfizer submitted data to the FDA showing that its updated version of the KP.2 vaccine increased antibody production in mice and provided better protection against JN.1 and its progeny than last year’s version of the vaccine.

Will the booster protect against infection or long-term COVID?

One of the biggest misconceptions about these vaccines is that they prevent infection, says del Rio. A common refrain is, “Well, they don’t work because I still got COVID.” It’s true that they aren’t great at preventing infection, he says, but that doesn’t mean vaccines aren’t working. “They are very good at preventing serious illness and mortality.”

It’s still not clear whether getting the vaccines will protect people from getting COVID long-term, says del Rio (SN: 17.7.24). Some data suggests yes, some suggests no. But, he says, “I think it’s a good idea to get vaccinated if you’re concerned.”

Talaat doesn’t see any real downside to getting the latest booster. “All vaccines have some side effects,” she says. People may see the same types of symptoms they experienced with earlier versions of the vaccine. They can include arm pain, headache, joint pain and fatigue. She points out that billions of vaccine doses have reached the arms of people around the world. “They are very confident,” she says.

Even if you’re young, healthy, and at relatively low risk, Talaat still recommends getting better. “We have to do what we can to protect ourselves and our loved ones,” she says. Talaat plans to vaccinate her two teenagers “because their grandparents are in their 80s,” she says, “and I want to make sure they stay safe, too.”

As for herself, Talaat says: “I’m seriously thinking about taking it next week.”

Erin Garcia de Jesús contributed to the reporting of this story.

#boosters #COVID19 #approved

Image Source : www.sciencenews.org